Let’s start with a scary number. The average dropout rates of doctoral students in Australia, the UK, Canada, and the US range somewhere between 30% to 50% (Glorieux et al., 2024). That basically means if two students start a PhD program together, there’s a pretty high chance that only one of them is going to walk away with the degree.

Why? Well, research shows one of the main reasons is a big gap between the goals and expectations students bring in versus the actual norms and practices of the discipline and department. And that mismatch can create a lot of frustration, stress, and eventually, for many… dropping out.

Why PhD is challenging

What makes a PhD one of the hardest marathons out there is that you really don’t see the end of it. Unlike undergrad where you know you need X credit hours and about four years, with a PhD you’re staring into the fog. You start with coursework, sure, but then you’re thrown into this massive, blurry world of research:

- Dive into a deep, narrow problem.

- Read almost everything you can get your hands on that’s ever been written about it.

- Find a knowledge gap.

- Then build a hypothesis (which is really just a fancy word for “here’s how I think I can fix this problem” and prove it with the scientific method.

Sounds neat, right? Except the reality is: it’s years of hitting walls, revising, and questioning yourself until you can’t tell the difference between healthy skepticism and… well, plain old self-doubt, which is the real trigger of imposter syndrome.

A bit about myself

So, quick background. Before starting my PhD in 2021, I was a structural engineer for ten years. Even during my master’s, I was still fully in the industry world. My life was simpler: problems show up, I fix them, I go home.

Then I stepped into academia, and suddenly I was in this mysterious realm where problems aren’t meant to be solved once, they’re meant to be dissected, traced to their root causes, broken into a thousand smaller pieces. And then, once you think you’ve got it figured out, you’re supposed to question yourself all over again.

My first real experiment? It took me two years of simulations, analysis, sleepless nights, and caffeine to even get to the testing stage. Near the end of my first year, I started realizing something, this habit of questioning everything… was bleeding into how I thought about myself.

How PhD can get you an imposter syndrome

What I found was that a PhD means constantly questioning your ideas, your methods, your results. And after a while, that loop of questioning turns inward. It’s not just “is my logic sound?” anymore, it’s “am I even good enough to be here?”

That’s exactly what happened to me. My brain, which was supposed to be skeptical about the research, turned on me personally. The thought “I am not good enough” started to creep in. Then came the fear of failure.

Soon after I joined my doctoral program, I spent the early months building up to my first experiment, and instead of being excited, I started hoping it would never happen. Why? Because if it failed, I thought it would prove that I didn’t belong. That fear turned into procrastination and avoidance. And the less progress I made, the more guilt I felt. Classic vicious cycle.

It wasn’t until the summer of my first year that I realize, this wasn’t just “me being me.” This was something that had been studied, written about, and even named, it was the Imposter Syndrome what I am experiencing.

What is imposter syndrome anyway?

Imposter Syndrome isn’t new. Back in 1978, psychologists Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanne Imes studied a group of high-achieving professional women. These women were brilliant, talented, objectively successful, but they constantly felt like frauds. They lived in fear of being “found out.” At the time, it was called the Impostor Phenomenon. Later, the name shifted to “syndrome” (maybe because it sounds more official, or cooler?).

Research shows imposter syndrome thrives in places where success is vague and hard to measure. Academia is a typical example. Success is long-term, subjective, and full of waiting. Nothing is immediate. It can take years to know whether your hypothesis holds up. That’s perfect soil for self-doubt, procrastination, and guilt.

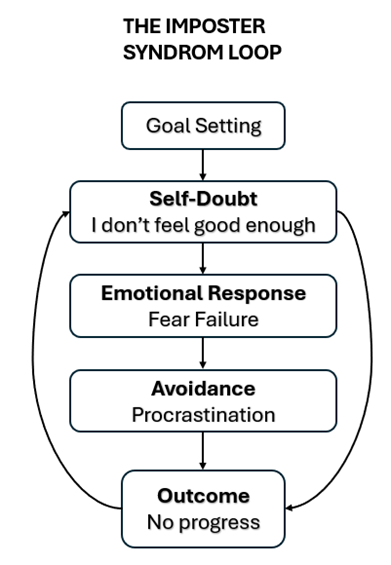

In my own way, I mapped it out like this (engineer brain here):

- You set a goal (write a paper, run an experiment).

- Self-doubt whispers, “Are you even capable of this?”

- Fear of failure starts growing.

- You procrastinate or avoid the task.

- Progress stalls → guilt rises.

- Cycle repeats.

If you’ve ever been stuck in that loop, welcome to the club.

How did I overcome imposter syndrome and how can you overcome it?

Once I named it, I realized something important: if I just accepted this cycle, it would become my default mindset. And that scared me more than any failed experiment.

So, I asked myself, why didn’t I feel this way back in industry? I handled tough projects, interdisciplinary teams, insane deadlines, and yet never once felt like an imposter.

The difference? Taking action.

In industry, I put in effort, and I saw results quickly: design a fix → it gets built → problem solved. That feedback had built confidence, which fuels more action. Positive psychology actually has a name for this: the adaptive confidence loop.

So I rebuilt that loop inside my PhD. How?

- While others avoided writing, I went to my advisor and initiated ideas to work in several papers at a time.

- I pushed myself to juggle experiments and brainstorm the next ones simultaneously.

- I asked for feedback constantly, even when it stung.

- I treated setbacks as data points, not proof that I was a failure.

And slowly… it worked. The small actions led to progress, progress fueled confidence, and confidence made me take even more action. That momentum kept me going.

Funny enough, people warned me, “You’re going to burn out working this hard.” But honestly? I never felt it. The progress itself was energizing.

Final Thoughts

Imposter syndrome is real, and if you don’t confront it, it can swallow your confidence, your motivation, and maybe even your PhD. But it’s not unbeatable.

If you focus on creating small, tangible wins, building your own feedback loops, and remembering that self-doubt ≠ incompetence, you can flip the script.

One more fact from positive psychology, Teresa Amabile’s research shows that tracking small wins makes people 46% more likely to stay motivated and engaged in their work. That’s huge. So celebrate the baby steps, they’re the antidote to feeling like a fraud.

At the end of the day, imposter syndrome doesn’t mean you don’t belong. It just means you’re stretching, you’re growing, and your brain hasn’t caught up yet. And yes, you can beat it.

References

Glorieux, A., Spruyt, B., Minnen, J., & van Tienoven, T. P. (2024). Calling it quits: a longitudinal study of factors associated with dropout among doctoral students. Studies in Continuing Education, 47(1), 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2024.2314694

Amabile, T. M., & Kramer, S. J. (2011). The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement, and Creativity at Work. Harvard Business Review Press.